The following article is long, and about a year old now, but the lessons in it are just as valuable today. If the folks on that tourist dinner cruise last week had read this, they might still be around. I think this is a brilliant piece of work, absolutely first-rate. And in this age of terrorism, the information presented here is spot-on timely and useful, but only if you read it, think about it, and put into practice its recommendations.

No one can predict an instananeous disaster, so what's the best way to prepare oneself for that eventuality? Simple: think a bit about what you'd do if the unthinkable happened. Find the exits in the theater. Sit with your back to the wall and facing the door of the restaurant. There are a million little ways you can prepare yourself mentally to save yourself in an instant. But it'll only work if you're ready to do it.

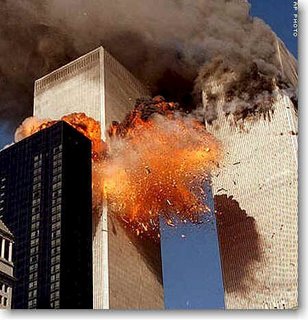

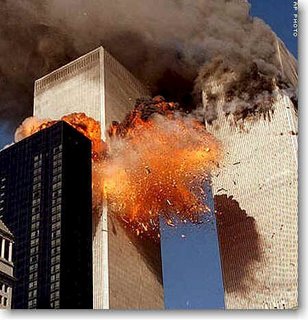

(Photos are not original to the article.)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

How to Get Out Alive

From hurricanes to 9/11: What the science of evacuation reveals about how humans behave in the worst of times

By AMANDA RIPLEY

May 2, 2005

When the plane hit Elia Zedeno's building on 9/11, the effect was not subtle. From the 73rd floor of Tower 1, she heard a booming explosion and felt the building actually lurch to the south, as if it might topple. It had never done that before, even in 1993 when a bomb exploded in the basement, trapping her in an elevator. This time, Zedeño grabbed her desk and held on, lifting her feet off the floor. Then she shouted, "What's happening?" You might expect that her next instinct was to flee. But she had the opposite reaction. "What I really wanted was for someone to scream back, 'Everything is O.K.! Don't worry. It's in your head.'"

She didn't know it at the time, but all around her, others were filled with the same reflexive incredulity. And the reaction was not unique to 9/11. Whether they're in shipwrecks, hurricanes, plane crashes or burning buildings, people in peril experience remarkably similar stages. And the first one--even in the face of clear and urgent danger--is almost always a period of intense disbelief.

Luckily, at least one of Zedeño's colleagues responded differently. "The answer I got was another co-worker screaming, 'Get out of the building!'" she remembers now. Almost four years later, she still thinks about that command. "My question is, What would I have done if the person had said nothing?"

Most of the people who died on 9/11 had no choice. They were above the impact zone of the planes and could not find a way out. But investigators are only now beginning to understand the actions and psychology of the thousands who had a chance to escape. The people who made it out of the World Trade Center, for example, waited an average of 6 min. before heading downstairs, according to a new National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) study drawn from interviews with nearly 900 survivors. But the range was enormous. Why did certain people leave immediately while others lingered for as long as half an hour? Some were helping co-workers. Others were disabled. And in Tower 2, many were following fatally flawed directions to stay put. But eventually everyone saw smoke, smelled jet fuel or heard someone giving the order to leave. Many called relatives. About 1,000 took the time to shut down their computers, according to NIST.

In other skyscraper fires, staying inside might have been exactly the right thing to do. In the case of the Twin Towers, at least 135 people who theoretically had access to open stairwells--and enough time to use them--never made it out, the report found.Since the early days of the atom bomb, scientists have been trying to understand how to move masses of people out of danger. Engineers have fashioned glowing exit signs, sprinklers and less flammable materials. Elaborate computer models can simulate the emptying of Miami or the Sears Tower, showing thousands of colored dots streaming for safety like a giant Ms. Pac-Man colony. But the most vexing problem endures. And it is not signage or architecture or traffic flow. It's us. Large groups of people facing death act in surprising ways. Most of us become incredibly docile. We are kinder to one another than normal. We panic only under certain rare conditions. Usually, we form groups and move slowly, as if sleepwalking in a nightmare.

Zedeño still did not immediately flee on 9/11, even after her colleague screamed at her. First she reached for her purse, and then she started walking in circles. "I was looking for something to take with me. I remember I took my book. Then I kept looking around for other stuff to take. It was like I was in a trance," she says, smiling at her behavior. When she finally left, her progress remained slow. The estimated 15,410 who got out, the NIST findings show, took about a minute to make it down each floor--twice as long as the standard engineering codes predicted. It took Zedeño more than an hour to descend. "I never found myself in a hurry," she says. "It's weird because the sound, the way the building shook, should have kept me going fast. But it was almost as if I put the sound away in my mind."

Had the planes hit later in the day, when the buildings typically held more than 32,000 additional people, a full evacuation at that pace would have taken more than four hours, according to the NIST study. More than 14,000 probably would have perished, Zedeño among them.

In a crisis, our instincts can be our undoing. William Morgan, who directs the exercise-psychology lab at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, has studied mysterious scuba accidents in which divers drowned with plenty of air in their tanks. It turns out that certain people experience an intense feeling of suffocation when their mouths are covered. They respond to that overwhelming sensation by relying on their instinct, which is to rip out whatever is in their mouths. For scuba divers, unfortunately, it is their oxygen source. On land, that would be a perfect solution.

Why do our instincts sometimes backfire so dramatically? Research on how the mind processes information suggests that part of the problem is a lack of data. Even when we're calm, our brains require 8 to 10 sec. to handle each novel piece of complex information. The more stress, the slower the process. Bombarded with new information, our brains shift into low gear just when we need to move fast. We diligently hunt for a shortcut to solve the problem more quickly. If there aren't any familiar behaviors available for the given situation, the mind seizes upon the first fix in its library of habits--if you can't breathe, remove the object in your mouth.

That neurological process might explain, in part, the urge to stay put in crises. "Most people go their entire lives without a disaster," says Michael Lindell, a professor at the Hazard Reduction & Recovery Center at Texas A&M University. "So, the most reasonable reaction when something bad happens is to say, This can't possibly be happening to me." Lindell sees the same tendency, which disaster researchers call normalcy bias, when entire populations are asked to evacuate.

When people are told to leave in anticipation of a hurricane or flood, most of them check with four or more sources--family, newscasters and officials, among others--before deciding what to do, according to a 2001 study by sociologist Thomas Drabek. That process of checking in, known to experts as milling, is common in disasters. On 9/11 at least 70% of survivors spoke with other people before trying to leave, the NIST study shows. (In that regard, if you work or live with a lot of women, your chances of survival may increase, since women are quicker to evacuate than men are.)

People caught up in disasters tend to fall into three categories. About 10% to 15% remain calm and act quickly and efficiently. Another 15% or less completely freak out--weeping, screaming or otherwise hindering the evacuation. That kind of hysteria is usually isolated and quickly snuffed out by the crowd. The vast majority of people do very little. They are "stunned and bewildered," as British psychologist John Leach put it in a 2004 article published in Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine.

So what determines which category you fall into? You might expect decisive people to be assertive and flaky people to come undone. But when nothing is normal, the rules of everyday life do not apply. No one knows more about human behavior in disasters than researchers in the aviation industry. Because they have to comply with so many regulations, they run thousands of people through experiments and interview scores of crash survivors. Of course, a burning plane is not the same as a flaming skyscraper or a sinking ship. But some behaviors in all three environments turn out to be remarkably similar.

On March 27, 1977, a Pan Am 747 awaiting takeoff at the Tenerife airport in the Canary Islands off Spain was sliced open without warning by a Dutch KLM jet that had come hurtling out of the fog at 160 m.p.h. The collision left twisted metal, along with comic books and toothbrushes, strewn along a half-mile stretch of tarmac. Everyone on the KLM jet was killed instantly. But it looked as if many of the Pan Am passengers had survived and would have lived if they had got up and walked off the fiery plane.

Floy Heck, then 70, was sitting on the Pan Am jet between her husband and her friends, en route from their California retirement residence to a Mediterranean cruise. After the KLM jet sheared off the top of their plane, Heck could not speak or move. "My mind was almost blank. I didn't even hear what was going on," she told an Orange County Register reporter years later. But her husband Paul Heck, 65, reacted immediately. He ordered his wife to get off the plane. She followed him through the smoke "like a zombie," she said. Just before they jumped out of a hole in the left side of the craft, she looked back at her friend Lorraine Larson, who was just sitting there, looking straight ahead, her mouth slightly open, hands folded in her lap. Like dozens of others, she would die not from the collision but from the fire that came afterward.

We tend to assume that plane crashes--and most other catastrophes--are binary: you live or you die, and you have very little choice in the matter. But in all serious U.S. plane accidents from 1983 to 2000, just over half the passengers lived, according to the National Transportation Safety Board. And some survived because of their individual traits or behavior--human factors, as crash investigators put it. After the Tenerife catastrophe, aviation experts focused on those factors--and people like the Hecks--and decided that they were just as important as the design of the plane itself.

Unlike tall buildings, planes are meant to be emptied fast. Passengers are supposed to be able to get out within 90 sec., even if only half the exits are available and bags are strewn in the aisles. As it turns out, the people on the Pan Am 747 had at least 60 sec. to flee before fire engulfed the plane. But of the 396 people on board, 326 were killed. Including the KLM victims, 583 people ultimately died--making the Tenerife crash the deadliest accident in civil aviation history.

What happened? Aren't disasters supposed to turn us into animals, driven by instinct and surging with adrenaline?

In the 1970s, psychologist Daniel Johnson was working on safety research for McDonnell Douglas. The more disasters he studied, the more he realized that the classic fight-or-flight behavior paradigm was incomplete. Again and again, in shipwrecks as well as plane accidents, he saw examples of people doing nothing at all. He was even able to re-create the effect in his lab. He found that about 45% of people in his experiment shut down (that is, stopped moving or speaking for 30 sec. or often longer) when asked under pressure to perform unfamiliar but basic tasks. "They quit functioning. They just sat there," Johnson remembers. It seemed horribly maladaptive. How could so many people be hard-wired to do nothing in a crisis?

But it turns out that that freezing behavior may be quite adaptive in certain scenarios. An animal that goes into involuntary paralysis may have a better chance of surviving a predatory attack. Many predators will not eat prey that is not struggling; that way, they are less likely to eat something sick or rotten that would end up killing them. Psychologist Gordon Gallup Jr. has found similar behavior among human rape victims. "They report being vividly aware of what was happening but unable to respond," he says.

In a fire or on a sinking ship, however, such a strategy can be fatal. So is it possible to override this instinct--or prevent it from kicking in altogether?

In the hours just before the Tenerife crash, Paul Heck did something highly unusual. While waiting for takeoff, he studied the 747's safety diagram. He looked for the closest exit, and he pointed it out to his wife. He had been in a theater fire as a boy, and ever since, he always checked for the exits in an unfamiliar environment. When the planes collided, Heck's brain had the data it needed. He could work on automatic, whereas other people's brains plodded through the storm of new information. "Humans behave much more appropriately when they know what to expect--as do rats," says Cynthia Corbett, a human-factors specialist with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

To better understand how the mind responds to a novel situation like a plane crash, I visited the FAA's training academy in Oklahoma City, Okla. In a field behind one of their labs, they had hoisted a jet section on risers. I boarded the mock-up plane along with 30 flight-attendant supervisors. Inside, it looked just like a normal plane, and the flight attendants made jokes, pretending to be passengers. "Could I get a cocktail over here, please? I paid a lot of money for this seat!"

But once some (nontoxic) smoke started pouring into the cabin, everyone got quiet. As most people do, I underestimated how quickly the smoke would fill the space, from ceiling to floor, like a black curtain unfurling in front of us. In 20 sec., all we could see were the pin lights along the floor. As we stood to evacuate, there was a loud thump. In a crowd of experienced flight attendants, still someone had hit his or her head on an overhead bin. In a new situation, with a minor amount of stress, our brains were performing clumsily. As we filed toward the exit slide, crouched low, holding on to the person in front of us, several of the flight attendants had to be comforted by their colleagues.

Remember: those were trained professionals who had jumped down a slide at some point to become certified. I could imagine how much worse things might go in a real emergency with regular passengers and screaming children. As we emerged into the light, the mood brightened. The flight attendants cheered as their colleagues slid, one by one, to the ground.

Mac McLean has been studying plane evacuations for 16 years at the FAA's Civil Aerospace Medical Institute. He starts all his presentations with a slide that reads IT'S THE PEOPLE. He is convinced that if passengers had a mental plan for getting out of a plane, they would move much more quickly in a crisis. But, like others who study disaster behavior, he is perpetually frustrated that not more is done to encourage self-reliance. "The airlines and the flight attendants underestimate the fact that passengers can be good survivors. They think passengers are goats," he says. Better, more detailed safety briefings could save lives, McLean believes, but airline representatives have repeatedly told him they don't want to scare passengers.

And so most passengers are indeed goats. Should the worst occur, says McLean, "people don't have a clue. They want you to come by and say, O.K., hon, it's time to go. Plane's on fire."

If we know that training--or even mental rehearsal--vastly improves people's responses to disasters, it is surprising how little of it we do. Even in the World Trade Center, which had complicated escape routes and had been attacked once before, preparation levels were abysmal, we now know. Fewer than half the survivors had ever entered the stairwells before, according to the NIST report. Thousands of people hadn't known they had to wind through confusing transfer hallways to get down.

Early findings from another study, sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control, found that only 45% of 445 Trade Center workers interviewed had known the buildings had three stairwells. Only half had known the doors to the roof would be locked. "I found the lack of preparedness shocking," says lead investigator Robyn Gershon, an associate professor of sociomedical sciences at Columbia University who shared the findings with TIME.

Until last year, it was illegal to require anyone in a New York City high rise to evacuate in a drill. That is absurd, of course. Under regulations being debated, building managers will probably have to run full or partial evacuation drills every two years so most people in those buildings will have entered their stairwells at least once. Some people may even descend to the bottom, and they will never forget how long it takes. The disabled will figure out how much assistance they need. The obese will see that they slow down the whole evacuation as they struggle for breath.

Manuel Chea, then a systems administrator on the 49th floor of Tower 1, did everything right on 9/11. As soon as the building stopped swaying, he jumped up from his cubicle and ran to the closest stairwell. It was an automatic reaction. As he left, he noticed that some of his colleagues were collecting things to take with them. "I was probably the fastest one to leave," he says. An hour later, he was outside.

When I asked him why he had moved so swiftly, he had several theories. The previous year, his house in Queens, N.Y., had burned to the ground. He had escaped, blinded by smoke. Oh, yes, he had also been in a serious earthquake as a child in Peru and in several smaller ones in Los Angeles years later. He was, you could say, a disaster expert. And there's nothing like a string of bad luck to prepare you for the unthinkable.